QUESTIONING JUSTICE

2020/21

One good reason to travel slowly is that you leave time to chance. An unexpected message catches your attention and suddenly your program for the day looks very different. Sometimes it will leave memories - and examples of courage - that will stay with you all your life.

This is how I discovered Maillé 9 years ago. I'm really not proud of the fact that it was only by accident. Once upon a time, I had heard the name - as the sister village of Oradour-sur-Glane – but since that day in 2012, the memory would be scratched on my retina.

Nazi barbarism took the lives of 643 victims in Oradour on June 10, 1944. The 643rd victim was only recognized in December 2019 by the Tribunal de Grande Instance de Limoges. She was identified thanks to the search work of the Catalan historian David Ferrer Revull and the "Ateneo Republicano du Limousin": the then 72-year-old Ramona Dominguez Gil who had fled Francoism there with her children and grandchildren and became one of the 19 Spanish victims in Oradour along with her grandchildren Miquel, Harmonia and Llibert, aged 11, 7 and less than 2 (source: Radio France Bleu Limousin 02 10 2020; Le Populaire du Centre 05 10 2020).

Every human life, every victim counts. Terror cannot be measured in numbers.

Some two months after Oradour, on August 25, 1944, 124 of the 500 inhabitants of Maillé lost their lives in a similar so-called punitive expedition of Nazi terror.

As in Oradour-Glane, Spanish refugees had found refuge in Maillé just before World War II, but judging by the names, none of them are among the 1944 victims there - although their fate is now being studied as well.

Unlike Oradour, Maillé was quickly rebuilt. Only two monuments, the cemetery and a museum remember it as a place of remembrance.

That small, quiet village is well worth your visit - a matter of respect and confrontation with our recent history.

For our American and English friends, I especially mention the aid of the philatropist couple of Girard Hale and Kathleen Burke.

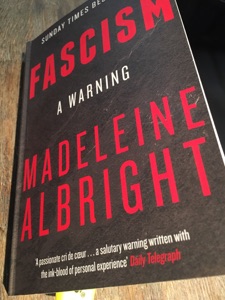

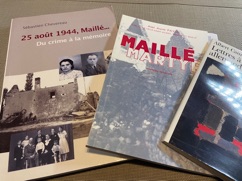

For all the historical sources of this piece, I thank Romain Taillefait, director of 'La Maison du Souvenir' of Maillé (link here), and the authors Sébastien Chevereau ('25 août 1944, Maillé. Du crime à la mémoire') and (late) Abbé André Payon ('Maillé Martyr')

On the road to Maillé

Perhaps you lack the time to stop on the road in France. Maybe. Maybe you think there is little travel time left in times with Corona, that it is difficult to plan, and that it is best to arrive at our southern destination as quickly as possible. All understanding of that.

So let me first formulate it - irreverently - as a tourist tip. The best way to get sunshine from Flanders to the south is to avoid Paris and its surroundings. A wide bend brings you along Rouen, Tours, Poitiers, Limoges. Take your time: your vacation starts on the road, but so does your journey to learn.

Thus, on August 30, 2012, we were on our way to Tours, with a second stage near Limoges the following day, to visit Oradour-sur-Glane a second time. Yes, because the first time we were really young. So young, in fact, that I was still photographing with my eyes.

That afternoon in 2012, we habitually listened to Radio France Inter's "La Marche de l'histoire" by Jean Lebrun, about .. ‘Le massacre de Maillé, un autre Oradour’ (link here). It became very quiet in the car for 29 minutes.

Days later, a monument on the right side of the Route Départementale 910 (formerly the legendary Route Nationale 10) caught my attention. Something in the back of my mind reminded me of the radio broadcast from the day before. The brakes slammed shut and verified: the flowers from the memorial ceremony a few days before were still fresh and the inscription confirmed: 'Maillé à ses 124 martyrs'.

Without looking for Maillé, Maillé had found us - a bit like we saw the signpost and the island of 'Utoya' looming years later in Norway - in a far-right historical extension, lugubriously topical.

Opened in 2008, Maillé's 'La Maison du Souvenir' is modern and small (200m2) and thus suitable for a short visit but very interesting, and you will be received very attentively.

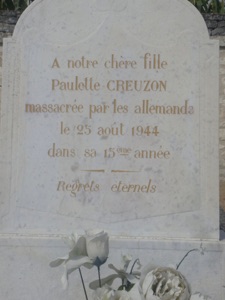

Don't forget to visit the cemetery and dwell there on the names of the victims, with their ages on the individual graves with the same date of death on August 25, 1944: from 3 months to 89 years.

Maillé during the war

Maillé is a small farming village of about 500 inhabitants that had already made its sacrifices long before 1944: 23 died in the First World War.

During the German offensive of World War II, 21 inhabitants were taken prisoner of war. Just because their liberation was delayed until 1945, they were "saved" from the massacre in 1944.

In June 1940, the French government of President Albert Lebrun left Paris for Tours, and on June 14, the headquarters of the Third Republic headed south for Bordeaux: the motorcade passed Maillé on the then National 10, then of course still without the 1944 monument (erected in 1947).

On June 20, 1940, the convoy of General Huntziger, who was to sign the Armistice by order of Philippe Pétain, was again heading north along Maillé on the same Nationale 10.

Huntziger will sign the "Statut des Juifs" a few months later, on October 3, 1940, together with Pétain and Laval in Vichy - applicable at that time to about 150,000 French subjects.

The Indre-et-Loire département is then divided in two, and Maillé falls into territory directly occupied by Nazi Germany, close to the demarcation line with the so-called 'Zone Libre'. The Paris-Bordeaux railroad line (already built under the Second Empire) that passes in Mailly and the nearby Nouâtre military camp make it a strategic zone.

After the Spanish refugees of 1939, in 1940 the area around Maillé had up to a thousand refugees - probably including Belgians, like my father and father-in-law - whom the Germans were slow to allow to return. Then, the occupying forces obliged the small village to maintain about 150 German soldiers (with their 169 horses!).

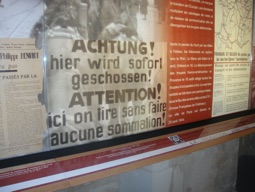

On December 29, 1940, a first act of resistance takes place in Maillé: a military telephone cable is sabotaged. Five German posters threaten the population with severe punishment but the culprit is not found.

The French pastor who studied in Leuven and was buried as a Belgian worker.

It is Henri Péan, the parish priest of Draché, Maillé, and La Celle-Sant-Avant (who studied at the Belgian University of Leuven-Louvain) who will become one of the most important resistance fighters of the region. After a short period of captivity, he was able to return to his parish for the celebration of Christmas 1940.

His extravagance as a motorcyclist and car driver had already earned him the nickname "Péan le Fou".

As a priest, he possessed an "Ausweis" to cross the demarcation line into the so-called "Free Zone", but more often this was done at night, as a 40 km walk.

In a letter anno 1941 from a resistance woman (who later went into hiding), Péan is described as "très sympathique par ses sentiments vraiment français. C'est un chic type à ce point de vue et il serait à souhaiter que tout le clergé pense pour lui". With that last wish, legitimate doubts are echoed about the French conservative clergy, which often stood behind Pétain with his paternalistic slogan "Famille, Patrie, Travail,".

In the same letter her anger about Marshal Pétain is heard "...je bous de rage et d'indignation. Quel vieux fourbe ou vieux gâteux, on ne sait! En tout cas sa conduit est heuteuse et indigne d'un officier français. Il ment comme 'ses maîtres, les Allemands".

Péan, through his network, will send some 100 downed English, Canadian and American pilots - as well as Jews in hiding - into hiding and provide them with food and false papers.

In July 1943, he organized the first parachutings of weapons in his region, announced via the BBC with the message "Il faut des chrysanthèmes pour la Toussaint”.

However, the Sipo-SD and the Gestapo got on Péan's trail, arresting him on February 13, 1944 after his church service in Celle-Saint-Avant. Pastor Henri Péan was tortured during fourteen days in the Gestapo's premises in Tours, but is said to have been killed by his German interrogator in a moment of anger - that is, unintentionally - on February 27 or 28, 1944.

The Germans, worried about the population's reaction to the death of the populist "abbé Péan", decided to conceal the crime by burying him the "Cimetière de La Salle" of Tours under the false name of a Belgian worker, Henri Verdier.

This second crime is not discovered until 1948, and the following year, Father Péan is interred in the family tomb in Draché.

Maillé on August 25, 1944

It would be disrespectful to the victims to try to recount in this short article what happened that day.

Therefore, I only summarize the framework, matter of sending you on your way to Maillé.

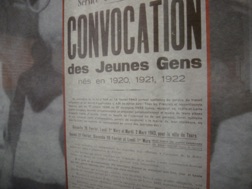

The disembarkations of the Allies on June 6 in Normandy and on August 15, 1944 in Provence dramatically change the war situation in France. The German troops in Bordeaux and Nantes must fold back northward to the Loire and thus return via the same Route Nationale 10 and the Bordeaux-Paris railroad.

The Maquisards will put pressure on this tactical return by a multiplied effort in the Tourraine: this is also the order of the inter-Allied command.

Around Maillé, therefore, at least 15 acts of sabotage by various resistance groups take place between August 8 and 24. Three times the railroad line in Maillé explodes: on August 14 and 15 and in the night of August 22-23, 1944.

In the evening of August 24, two German military vehicles come under fire in the hamlet of Nimbré of Maillé. Doctor Barbot - who claims to have been obliged with the mitraillette on his forehead to take care of a wounded German – mentioned to a patient that an officer told him "Tomorrow we will make that Maillé pay".

What would have prompted the massacre remains a mystery. In nearby Loche, the Nazis had already taken hostages among the population in mid-August and threatened to burn the town to the ground in case of an attack by the resistors - causing the resistance group Epernon to withdraw there on August 23-24.

On August 25, the massacre starts on the farms "La Heurtelière" and "Le Moulin" just outside Maillé: not only are all the men, women and children murdered in cold blood, but so is everything that lives, from horses, cows and sheep to chickens, dogs and cats. The two farms were set on fire around half past nine, after which the 17th SS Panzer Genadier Division - some 60 soldiers - entered Maillé.

Civilians raised white flags and shouted "Civil Kamerade!" but were shot, beaten to death or stabbed to death with the baïonette at such close range that the wounds looked like explosions - so writes Sébastien Cheverau in his work.

One of the miraculous survivors, Suzanne Meunier, then 23, testified to the French Gendarmerie shortly afterward how an SS man first reloaded to shoot her infant daughter dead and then shot at her infant son whom she held in her arms. She herself badly wounded, gestured to be death and later, dragged herself out of the burning house and hid in the garden.

At noon, a blanc cannon shot signals the retreat of the killer gang. Then, from 2 p.m., a bombardment starts: 80 shells fall on this village of 60 houses, almost all of which are already ablaze by then...

Among the 124 people killed, 44 were children under 14.

And a Belgian victim wanted by the Nazis ...

René Jamin was born in Halanzy, on the Belgian side of the border triangle with France and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. He completes his military service in Arlon but settles as a charcutier on the French side of the border, in Lucquy. With the French army, he defended the port of Dunkirk in 1940 and was severely wounded twice.

After his return to Lucquy, he resumed his work but also joined the resistance (reception of Allied pilots, sabotage of railroad lines). Wanted there by the Nazis, he finds refuge in Maillé as an employee of the Dupin company that is supposed to maintain the Paris-Bordeaux railroad line. Perhaps he joins the resistance group Conty-Freslon in the summer of 1944.

On that railroad line, two sabotages are carried out on August 20 and 23, 1944.

Together with two other workers from the Dupin company, Jamin was in Maillé's café Métais at the time of the German raid. Together with other clients he hid in the cellar of the café, where everyone was discovered and killed under machine gun fire (source Maitron.fr dictionnaire biographique fusillés, guillotinés, exécutés, massacrés 1940-44).

So in his case, the Nazis here never found out who they had killed.

No conviction, or hardly any....

Maillé is mentioned in the 1946 Nurenberg trial and in a French proceeding at the permanent military court of Bordeaux that leads to one conviction (to the death penalty) in 1952 for the Maillé massacre, that of Lieutenant Gustav Schlüter. However, Schlüter fled to the Soviet-occupied zone immediately after his interrogation in 1950 and was never extradited afterwards, even when he returned to what was then West Germany. He died peacefully in Hamburg in 1965.

Starting in 2005, the Dortmund public prosecutor's office opened a new investigation, but it was filed in 2017 without result.

Meanwhile, the Permanent Military Court of Paris had tried the Gestapos operating in Tours who were responsible for the martyrdom of Father Péan.

That trial was made possible by an action of the resistance group of Jean Meunier (later mayor of Tours) who captured the archives of the Sipo-SD in Tours and was thus able to preserve part of the interrogations of the group around Henri Péan.

In 1954, three leaders of the Gestapo, the administrative police and the German judicial police of Tours were convicted in absentia. They too had previously disappeared into the Soviet zone during the Cold War.

For that collaboration in Tours, the execution of French translater Vladimir Gontcharoff, ordered by the Cour de Justice de Tours, was carried out on July 13, 1945.

Another translator who worked for the Gestapo of Tours, Clara Knecht - alias "La Chienne" because of her doggedness - had just before been sentenced to death by the Cour de Justice of the Indre-et-Loire on April 6, 1945, but was finally found to have already perished on January 25, 1945 in the bombing of Pforzheim.

Today and tomorrow: the duty never to forget.

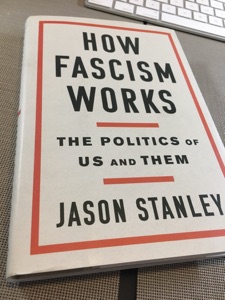

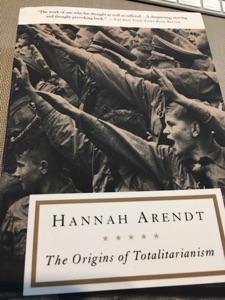

Maillé reminds us of what humans are capable of: for better, and for worse. The atrocities in Maillé are those of today still elsewhere in the world.

The courage of resistance to the barbarism of then, is the courage of now against the threats of today.

In the conclusion of "Indignez-vous !" Stéphane Hessel recalled that the threat of Nazism has not completely disappeared. Hessel called for a new resistance, against oblivion, against that amnesia.

Stop for a moment in Maillé. Keep the memory intact. Keep the resistance alert.

The martyrs of Maillé

24 augustus 2021

Henri Péan, the parish priest (who studied at the Belgian University of Leuven-Louvain) became one of the most important resistance fighters of the region.

His extravagance as a motorcyclist and car driver had already earned him the nickname "Péan le Fou".