Twitter case

2020-21

Twitter case #justicewatcher v. Flemish minister of Justice and Enforcement Zuhal Demir

Dear colleagues at the

-

•Flemish Union of Journalists (Vlaamse Vereniging van Journalisten @vvjournalisten)

-

•European Federation of Journalists (@EFJEUROPE)

-

•European Centre for Press and Media Freedom (@ECPMF)

-

•Index on Censorship (@IndexCensorship)

-

•Cc Council of Europe Platform for the Protection of Journalism and Safety of Journalists (@CoEMdediaFreedom)

I hereby formally confirm and further document the complaint I filed at the reporting point of the Flemish Union of Journalists (Vlaamse Vereniging van Journalisten - VVJ)

My complaint raises fundamental questions about the blocking on social media of citizens and journalists by politicians (and particularly members of the Executive Branch).

In my view, supported by jurisprudence, fundamental rights as the freedom of speech and the press’s watchdog function are here at stake.

This is a very long read, so let me just present the contents:

-

•The parties involved now in this case #justicewatcher v. Flemish minister of Justice and Enforcement Zuhal Demir

-

•Summary of this case

-

•The practical consequences of blocking on Twitter

-

•The official nature of the Twitter account of minister Zuhal Demir

-

•The importance of Twitter for Citizenship

-

•The even greater importance of Twitter for journalism: free press

-

•The ‘chilling effect’ of being blocked by officials

-

•The first Twitter alternative for minister Demir: unfollowing

-

•The second Twitter alternative: muting

-

•The fundamental rights at stake because of the blocking: the example of Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University v. Donald. Trump, President of the United States

-

•The plaintiffs

-

•The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University

-

•The individual plaintiffs in that American case against President Trump were very diverse

-

•The Order of Judge Buchwald on May 23rd 2018 was clear

-

•That judgement was affirmed on July 7th 2019 by the Second Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals

-

•“Censor”, voilà the key word

-

•The affirmation of the judgment of the District Court could not end on a more eloquent note by Circuit Judge Barrington D. Parker

-

•The ‘en banc hearing’ by the Court of Appeals, demanded by President Trump, was rejected on March 23rd 2020 by a vote of 7 – 2

-

•Since then, President Trump filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with The Supreme Court

-

•Idem for Facebook

-

•Back to Flanders, Belgium, thanks to this ‘Cosmopolitan First Amendment’: our own Constitution, our key laws on this matter, but also basic human rights, checked by the European Court of Human Rights (Strasbourg)

-

•The sources of our law, safeguarding free speech and free press

-

•The procedure: ‘see you in court’ ?

-

•The Dutch example

-

•The archives of Twitter

-

•An illustration about this aspect in Antwerp: historians erasing history

-

•Last, but not least, this leads us to the democratic aspect

-

•Miami Mayor Philip Levine, a Democrat

-

•Kentucky Governor Matt G. Bevin, a Republican

-

•In Canada, Jim Watson, the mayor of Ottawa

-

•Therefore, this is still first an appeal: let’s talk !

-

The parties involved

Out of courtesy for mrs. Demir, I present the ‘defendant’ first:

Mrs. Zuhal Demir (Twitter @Zu_Demir) is a member of the Flemish nationalist and separatist party N-VA and became on Oct. 2nd 2019 the first Flemish ‘minister of Justice and Enforcement’ - with limited areas of competence.

Indeed, Belgium still has also a federal secretary of State (minister) of Justice, with much larger areas of competence.

The other Flemish competences of minister Demir are the Environment, Energy and Tourism.

Mrs. Demir is a lawyer (master in Law at KULeuven and master in Social Law at VUB) since 2004.

She was elected for the N-VA as a Member of Parliament since 2010.

From 2013 till 2017 she chaired the Flemish government's integration strategy Agency.

In the previous federal government, she was State Secretary for Poverty Reduction, Equal Opportunities, People with Handicap, Urban Policy and Scientific Policy

from 2017 till the end of 2018.

As ‘plaintiff’, I must introduce myself, Jan Nolf (Twitter @NolfJan)

I worked 10 years as a lawyer (master in Law and in Criminology, UGent), followed by 25 years as a judge. I retired at 60 to write and joined Twitter as #justicewatcher (website Justwatch) in 2012 to accompany my new work as an author and journalist on legal, political and social topics (also manuals about the legal protection for people with a handicap).

Between my almost 10.000 followers, you find many politicians, academics and journalists.

In 2016, the Foundation P&V awarded me its Citizenship Award ‘in tandem’ with the Brussels judge Michel Claise, famous for his quest against financial and fiscal fraud.

The (then) federal minister of Justice and law professor (KULeuven) Mr. Koen Geens sent me on Nov. 28th 2016 a letter with congratulations, mentioning “your important voice, caring for justice, with particular attention for vulnerable citizens is more than heard and fully valued. That you, as a prominent magistrate and columnist in the public debate, continue to strive for an improvement of the judicial system and an open, democratic and solidary society, forces our respect. (…) I wish you much success with your new book ‘The force of justice’ “

Summary of this case

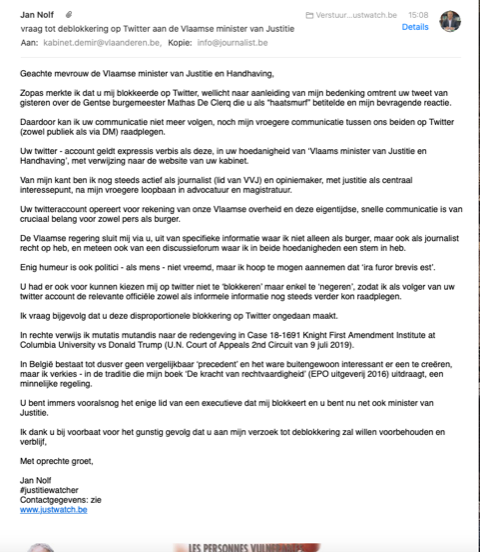

Mrs. Demir and I followed each other already some years on Twitter, before she became on Oct. 2nd 2019, the first Flemish ‘minister of Justice and Enforcement’ We had a number of public and private (DM) exchanges.

On Sept. 28th 2020, I discovered Mrs Demir had blocked me on her official account @Zu_Demir

This account with 45.000 followers is the official account of the minister, announced as ‘Vlaamse minister van Justitie en Handhaving, Omgeving, Energie en Tourisme – and the summary of its profile mentions her cabinet (‘vragen via kabinet.Demir@vlaanderen.be ‘)

I can only guess the decision of the minister was inspired by an incident on Sept. 27th 2020, following her insult on Twitter, decribing Mr. Mathias De Clercq, mayor of Gent as a “stokende haatsmurf” (‘hate stoking Smurf’).

That Sunday, mr. De Clercq had criticized with some sarcasm (“Eindelijk samen, eindelijk verenigd. Eindelijk thuis” – ‘finally together, finally united, finally home’) the presence of members of her own party N-VA at the far-right (car rally) meeting of the Flemish extremist party Vlaams Belang (against the new federal ‘Vivaldi’ government) the day before in Brussels – a meeting Mrs Demir defended as “people who are rightfully angry”).

I challenged Mrs. Demir by citing Bart De Wever, the president of her own Flemish nationalist party who had warned just recently on television (VRT 7Dag) against “cafépraat’ (in fact his own ‘cafe talk’) and was quoted in the newspaper De Standaard about his own party members as “Hou jullie een beetje in” (‘hold back a bit’).

My tweet started with the informal “Allez Zuhal” (‘Come on Zuhal…’), which is not to be considered aggressive at all, but a poking appeal to calm down.

Apparently, the minister blocked me immediately, without any response.

That same Sept. 28th, I sent a mail, expressing also comprehension for some anger on her side (‘ira furor brevis est’), but to no avail.

Apparently, the minister couldn’t appreciate being reminded by me of the own warnings of the president of her own party. Anyway, there is no doubt my tweet(s) did not engage in any category of speech that could be considered as justifying that kind of action by a government official.

Why was minister Demir in my case so short tempered that day, when the president of her own party N-VA commented “To be insulted is the price of liberty and we pay this price with pleasure (comment of 13/01/2015 on a GAL-cartoon in Knack magazine, comparing him to Hitler).

On the other hand, when I checked earlier the list of twitterers Mrs. Zemir followed – and probably still follows - you find on the contrary, real examples of obscenity, defamation, fake news, and hate.

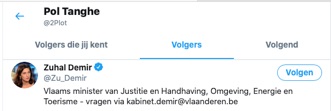

An interesting example of a Twitter account the Flemish minister of Justice followed was @2Plot – an account that vanished from Twitter only mid November 2020.

In its edition of April 29th 2020, Knack magazine published the unmasking of that anonymous troll. It appeared to be a lawyer, also active as a ‘deputy judge’ at the Business Court of Ostend. Since 2011, he sent thousands of racist, sexist and other loathsome tweets around.

Anyway, how puzzling and contradictory this Twitter choice of a Flemish ‘minister of Justice and Enforcement’ may be, she is free to follow on Twitter whom she wants.

The only question I raise, is the (un)blocking of myself as a writer and journalist, specialized in law and ….. justice.

The practical consequences of blocking on Twitter

As I explained in my mail of Sept. 28th 2020 to minister Demir, a blocking on Twitter has many consequences.

Not only you cannot read any more the tweets of the person or organization who’s denying you access.

More, you lose all Twitter information - directly sent by the person who blocks you - not only from the blocking on, but also all his tweets in the past.

That wall goes up for for all public as well the (private) Direct Messages that were exchanged.

Furthermore you lose all possibility for the essence of the Twitter platform: interaction.

You cannot ask any questions anymore to that account. You cannot retweet with a comment, nor ‘like’.

The twitterer who blocks you can comment on you (and frequently does), but you are not – at least not directly – aware of those cowardly attacks behind your back.

Even if you can see interactions of others, with the person/organization who blocked you, the line of communication is broken, and you cannot verify the initial tweet: you are in the dark, you are ‘out’ – outlawed on Twitter.

The official nature of the Twitter account of minister Zuhal Demir

In the same mail of Sept. 28th 2020 to minister Demir, I pointed out the official nature of her Twitter account expressis verbis in her official capacity as the Flemish minister of Justice and Enforcement, explicitly mentioning the website of the Flemish administration.

Even if politicians often use their official social media accounts to publish messages related to their own party politics on one hand but also promotion of (public) aspects of their family life on the other hand, there can be no doubt that this Twitter account is operational as the only Twitter account of minister Demir in her official function.

As in the case of Knight First Amendment Institute At Columbia University e.a. v. Donald J. Trump, President of the United States (Case 1;17-cv-05205 US District Court for the Southern District of New York), our Flemish minister of Justice and Enforcement Zuhal Demir uses that account “to announce, describe and defend (her) policies, to promote (her) Administration’s legislative agenda; to announce official decisions; to engage with (…) political leaders; to publicize (…) visits; to challenge media organizations whose coverage of (her) Administration (she) believes to be unfair; and for other statements, including on occasion statements unrelated to official government business.” (p. 10/75)

In her Order of May 23rd 2018 in that case, Judge Buchwald added “President Trump sometimes uses his account to announce matters related to official government business before those matters are announced to the public through other official channels” – a practice we often also see in Belgian politics.

That’s exactly why all professional news media follow politicians and especially Cabinet members. The news does not first come from press releases or the Belgisch Staatsblad (‘Belgian Official Gazette’) but from Twitter.

There is a difference indeed, with lawmakers in general and members of the Executive Branch. Ministers and secretaries of State do more than ‘politics’ in the partisan meaning of the word, they make decisions, impacting our everyday life and they inform the public on them, sometimes in a ‘fast and furious’ way via Twitter.

The importance of Twitter for Citizenship

In their first Complaint, filed on July 11th 2017 in the case of Knight First Amendment Institute At Columbia University e.a. v. Donald J. Trump, President of the United States, the plaintiffs argued:

“As the Supreme Court recognized just a few weeks ago, social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter provide ‘perhaps the most powerful mechanism available to a private citizen to make his voice heard’ - Packingham v. North Carolina. These platforms have been ‘revolutionary’, not least because they have transformed civic engagement by allowing elected officials to communicate instantaneously and directly with their constituents. (…) Twitter enables ordinary citizens to speak directly to public officials and to listen to and debate others about public issues, in much the same way they could have gathered on a sidewalk of in a public park, or at a city council meeting or town hall.”

U.S. District Judge Naomi R. Buchwald agreed in her Memorandum and Order of May 23rd 2018 (p. 5-6 of 75) that

“a defining feature of Twitter is a user’s ability to repost or respond to others’ messages and to interact with other Twitter users in relation to those messages. (…) The collection of replies and replies-to replies is sometimes referred to as a ‘comment thread’. Twitter is called a ‘social’ media platform in large part because of comment threads, which reflect multiple overlapping ‘conversations’ among and across groups of users”.

The even greater importance of Twitter for journalism: free press

This point is evident and crucial. Twitter largely outpassed Twitter.

Especially in this Trump-era, news on television and headlines in newspapers often start or are documented by tweets of the politicians concerned. Not seldom, a tweet is treated as #BreakingNews on itself.

Never in history, news – or what is considered as such – traveled so fast, and this is without any doubt thanks to social media.

The speed by which news items (facts, comments… ) are produced by the Second Branch of Government (the executive) demand an equally fast fact checking by the press – in its role as the ‘Fourth Branch’ in the checks and balances of democratic government and rule by law.

This is especially urgent in the new era of #FakeNews, as ‘False News Speeds Faster and Wider’ (Steve Lohr, citing M.I.T. research in the NYT of March 8th, 2018).

This task is rendered practically impossible for journalists who are blocked.

It is as if they were – several times a day – physically thrown out of crucial press conferences: cf. the lawsuit CNN filed in 2018 against the White House for revoking the press credentials of its chief White House correspondent, Jim Acosta.

President Judge Timothy J. Kelly of United States District Court in Washington D.C. ruled that the White House had behaved inappropriately in stripping Mr. Acosta of his press badge after a testy exchange at a news conference. The judge ordered the Trump administration to restore the press credentials of Jim Acosta of CNN.

Although the nature of the ruling was very limited ("it was not meant to enshrine journalists’ right to access and it was not determined that the First Amendment was violated here"), it still is worth mentioning here.

After a block in Twitter, you can’t ‘follow’ anymore: not on Twitter, but you can neither in the real world of speedy journalism. The tweets of minister Demir might be ‘open to all’ but not to you. Likes and retweets are barred and you need workarounds such as logging out or creating a new (anonymous) profile.

When you are blocked, you lack the original source: the person/organization who declared this or that – what others (whom you still can read) comment on. But you are excluded from doing the essence of this job: to check the original source, to verify, as ‘words matter, facts matter’.

The most critical voices fall out in that virtual – but real – battle for democracy: the ‘checks and balances’ balance the other way, the way of the powerful.

Viewpoint discrimination is illegal according to art. 10 ECHR.

The specific motivating ideology or the opinion of the speaker can never be the rationale for the restriction:

“171. Public interest ordinarily relates to matters which affect the public to such an extent that it may legitimately take an interest in them, which attract its attention or which concern it to a significant degree, especially in that they affect the well-being of citizens or the life of the community. This is also the case with regard to matters which are capable of giving rise to considerable controversy, which concern an important social issue, or which involve a problem that the public would have an interest in being informed about. The public interest cannot be reduced to the public’s thirst for information about the private life of others, or to an audience’s wish for sensationalism or even voyeurism (see Couderc and Hachette Filipacchi Associés, cited above, §§ 101 and 103, and the further references cited therein).

172. It is unquestionable that permitting public access to official documents, including taxation data, is designed to secure the availability of information for the purpose of enabling a debate on matters of public interest. Such access, albeit subject to clear statutory rules and restrictions, has a constitutional basis in Finnish law and has been widely guaranteed for many decades (see paragraphs 37-39 above).

173. Underpinning the Finnish legislative policy of rendering taxation data publicly accessible was the need to ensure that the public could monitor the activities of government authorities.

(Satakunnan Markkinapörssi Oy et Satamedia Oy c. Finlande [GC ECHR 931/13 June 7th 2017], § 171- 173 )

Democracy dies in darkness (warns the NYT): that darkness is what some politicians create on Twitter by excluding journalists who dare to ask embarrassing questions, shedding light on shady politics, and checking in this the ‘res publica’.

Twitter becomes the ‘echo chamber’ of those critic-averse politicians. They favour a friendly or docile press: not the fourth Constitutional power, but a cherry-picked ally of the second one, the Executive.

Deb Roy, one of the authors of the M.I.T. report concluded in the NYT: “Polarisation has turned out to be a great business model” – for authoritarians and populists.

The ‘chilling effect’ of being blocked by officials

The consequences of being blocked by an ordinary citizen or by a member of the Executive Branch are quite different.

The ‘arrogance of power’ (in the warning of that legendary critical senator William Fulbright) throws you out of the Government’s line of communication. Impossible to raise directly a question, to object, to make a remark or to disagree.

As a citizen, and as even more as a journalist, you almost cease to exist.

A bit as in that French legal thriller by Yannik Chauvin: “Que ton nom ne soit plus” (‘May you name cease to exist’): you cease to exist.

But being blocked on Twitter does not stop with your own, personal discomfort as a citizen or a journalist.

The message is more than: “we don’t want you here on Twitter, you’re not one of us, we throw you out”.

That intimidation goes quickly around and further – as intended: it is chilling for others.

The first Twitter alternative for minister Demir: unfollowing

This could have been the very evident first step for the Flemish minister of Justice and Enforcement – even before the second step (muting).

Indeed, muted accounts that you follow, will still appear in your Notifications tab.

But for muted accounts that you do not follow, no replies and mentions will appear (says UsingTwitter).

I followed the Flemish minister of Justice but I’m perfectly OK with her own ‘unfollowing’: that’s essentially the choice everyone has on Twitter.

Also, even not following someone on Twitter, you can still read his tweets, as long as he doesn’t block you.

From the political or even the practical viewpoint, it’s perfectly understandable some politicians prefer not to (officially) follow a critic, although from time to time checking that account for his comments.

Minister Demir could have chosen this first path, but she did not: she wanted not only not to hear anything from me at all, she wanted to silence me.

The second Twitter alternative: muting

Muting was the evident and second step for or Flemish minister of Justice and Enforcement, before her abrupt decision to silence me by blocking.

Muting is a totally different approach: the mute button allows you to remove an account's Tweets from your timeline without unfollowing or blocking that account.

The advantage is that you will no longer receive push notifications from that muted account.

For the second time: I’m also OK with that !

There is no obligation for any politician to notice your tweets, let alone respond to them, just as there is no obligation for a politician to answer the phone if you call his or her office.

Even for a member of my Flemish Government, it is the right not to read the messages of a taxpayer who happens to be also a journalist, and publishing in her specific area of competence.

It tells something about that Government, but fine !

Mrs. Demir could have chosen this second path, but again, she did not: she preferred not to hear anything from me at all, as she brutally blocked me, without any reply, explanation or motivation.

The intent is clear: silencing a voice.

A minister of Justice, silencing a journalist dedicated to justice: il faut le faire.

May I add this about ‘muting’: in the case of ‘Knight First Amendment Institute At Columbia University v. Donald Trump, President of the United States’, judge Buchwald

“suggested at oral argument that the parties consider a resolution of this dispute under which the individual plaintiffs would be unblocked and subsequently muted, an approach that would restore the individual’s ability to interact directly with (including by replying directly to) tweets from the @realDonaldTrump account while preserving the President’s ability to ignore tweets sent by users from whom he does not wish to hear.”

No such agreement has been reached in that American case, neither, at this time in mine with minister Demir.

On September 28th 2020 I received an automatic confirmation of my mail, but no answer from the minister, neither from her spokesman, and neither from her administration.

The fundamental rights at stake because of the blocking: the example of Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University v. Donald. Trump, President of the United States.

The plaintiffs

The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University

The ‘Knight Institute’ (Twitter @knightcolumbia ) works to defend and strengthen the freedoms of speech and the press in the digital age through strategic litigation, research and public education.

The First Amendment is an essential part of the American ‘Bill of Rights’.

Its history in a nutshell (quote of the website of The White House): “One of the principal points of contention between the Federalists and Anti-Federalists was the lack of an enumeration of basic civil rights in the Constitution. Many Federalists argued that the people surrendered no rights in adopting the Constitution. In several states, however, the ratification debate in some states hinged on the adoption of a bill of rights. The solution was known as the Massachusetts Compromise, in which four states ratified the Constitution but at the same time sent recommendations for amendments to the Congress.

James Madison introduced 12 amendments to the First Congress in 1789. Ten of these would go on to become what we now consider to be the Bill of Rights”

Let us thus quote that fundamental First Amendment: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, of prohibition the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the tight of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”.

Those words sound familiar if you read any Constitution of any democratic country, or the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) or the European Convention of Human Rights (1950).

Those words and rights became truly cosmopolitan: “It reveals a cosmopolitan First Amendment that protects cross-border conversation, facilitates the global spread of democratic principles, recognizes expressive and religious liberties regardless of location, is influential across the world, and encourages respectful engagement with the liberty regimes of other nations. The Cosmopolitan First Amendment is the product of historical, social, political, technological and legal developments”

(Timothy Zick, The Cosmopolitan First Amendment. Protecting Transborder Expressive and Religious Liberties’, Cambridge University Press 2015).

However, this struggle goes on, more now than ever since the end of the Third Reich, with the new surge of populism and authoritarianism.

The noted lawyer and award-winning legal scholar Floyd Abrams quotes in ‘The Soul of the First Amendment’ (Yale University Press 2017) Justice Hugo Black: “The very reason for the First Amendment is to make people of the country free to think, speak, write and worship as they wish, not as the Government commands”.

Abrams notes that in what came to be known as F.D.R.’s ‘Four Freedoms Speech’ in 1941, the first freedom was the freedom of speech.

With Kathleen Sullivan, the former dean of the Stanford Law School he warns “Censorship is contagious. Permitting the Government to limit the speech of some, inevitably would risk the rights of all.”

The individual plaintiffs in that American case against President Trump were very diverse

Rebecca Buckwalter (@rpbp) is a writer and political consultant, Philip Cohen is a professor of sociology at the University of Maryland (@familyunequal ), Holly Figueroa is a political organizer and songwriter (@AynRandPaulRyan ), Eugene Gu is a resident in general surgery at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (@eugenegu ) Brandon Neely is a police officer (@BraondonTXNeely ), Joseph Papp is an anti-doping advocate and former professional cyclist (@joepabike ), Nicholas Pappas is a comic and a writer (@Pappiness ).

As a writer - though not yet a comic - I could fit in that list.

Anyway, you hardly can survive in the legal jungle without a sense of humor.

Humor is verbal gold. Humor unites us. Humor calms tensions, but humor has also that disarming touch of veracity.

I will never forget those beautiful moments, as when stand-up comedian Michael Van Peel invited me at Radio 1as his ‘Summer Guest, or when Bert Kruismans concluded his laudation at my Citizenship Award P&V : “Jan Nolf heard the voice of Stéphane Hessel”.

Jurists often skate only on the icy surface, stand-up comedians get to the core.

The Order of Judge Buchwald on May 23rd 2018 was clear

“While alternative means of viewing the President’s tweets exist, (the plaintiffs) cannot see the original tweets themselves when signed into their blocked accounts, and in many instances it is difficult to understand the reply tweets without the context of the original tweets” (page 21/75) (…)

Those limitations are also particularized, in that they have affected and will affect the individual plaintiffs in a ‘personal and individual way’ (…) and the ability to communicate has been and will be limited because of each individual plaintiff’s personal ownership of a Twitter account that was blocked.”

Judge Buchwald concluded “the (Twitter) speech in which the individual plaintiffs seek to engage is speech protected by the First Amendment” and is therefore “protected speech” (p. 37/75).

Those “replies to the president’s tweets remain the private speech of the replying user (and does not) render the reply government speech” (p. 56/75).

As President Trump’s Twitter account is “generally accessible to the public at large without regard to political affiliation or any other limiting criteria” Judge Buchwald compares it to “a park (that) can accommodate may speakers and, over time, many parades and demonstrations” (p. 57/75): “the interactive space is capable of accommodating a large number of public speakers without defeating its essential function (…) to allow private speakers to engage with the content of the tweet”.

So, this “interactive space is a designated public forum” (p. 61/75) and “the interactive space of the President’s tweets accommodates a substantial body of expressive activity (…) and constitutes a designated public forum” (p. 62/75).

Of course, admits Judge Buchwald, blocking is permissible in this designated public forum, although “only if they are narrowly drawn to achieve a compelling state interest” but “here the individual plaintiffs were indisputably blocked as a result of viewpoint discrimination” – and is impermissible under the First Amendment (p. 63/75).

Judge Buchwald concluded “The audience for a reply extends more broadly than the sender of the tweet being replied to, and blocking restricts the ability of the blocked user to speak to that audience” (p. 67/75).

“Recognizing the President’s personal First Amendment rights, he cannot exercise those rights in a way that infringes the corresponding First Amendment rights of those who criticized him” (p. 68/75) judge Buchwald wrote.

That judgement was affirmed on July 7th 2019 by the Second Circuit of the U.S. Court of Appeals

The Court also rejects the reply of the Trump Government that the plaintiffs can engage in ‘workarounds’ such as creating new accounts, logging out to view the President’s tweets and using Twitter’s search functions to find tweets about the President posted by other users with which they can engage.

Circuit Judge Barrington D. Parker wrote: “We do conclude that the First Amendment does not permit a public official who utilizes a social media account for all manner of official purposes to exclude persons from an otherwise-open online dialogue because the expressed views with which the official disagrees”.

Indeed “because the President (…) acts in an official capacity when he tweets, we conclude that he acts in the same capacity when he blocks those who disagree with hem” (p/ 19/29).

As a general matter “social media is entitled to the same First Amendment protections as other forms of media.” (p. 22/29).

It should be noted that in this procedure in appeal, the government did not challenge any more the District Court’s conclusion that the speech in which the individual plaintiffs seek to engage is protected speech: “instead, it argues that blocking did not ban or burden anyone’s speech” (p. 24/29).

Of course, the Court admits “the government is correct that the individual plaintiffs have no right to require the President to listen to their speech” but “the speech restrictions at issue burden (their) ability to converse on Twitter with others who may be speaking to or about the president. (…) Once he opens up the interactive features of his account to the public at large, he is not entitled to censor selected users because they express views with which he disagrees”” (p. 25/29).

“Censor”, voilà the key word

Even the Trump Government concedes those ‘workarounds’ burden the individual plaintiff’s speech (p. 26/29) notes the Court, remarking that “burdens to speech as well as outright bans run afoul of the First Amendment”.

Finally, “when the government has discriminated against a speaker based on the speaker’s viewpoint, the ability to engage in other speech does not cure that constitutional shortcoming”.

The affirmation of the judgment of the District Court could not end on a more eloquent note by Circuit Judge Barrington D. Parker

“The irony in all of this is that we write at a time in the history of this nation when the conduct of our government and its officials is subject to wide-open, robust debate. This debate encompasses an extraordinary broad range of ideas and viewpoints and generates a level of passion and intensity the likes of which have rarely been seen. This debate, as uncomfortable and as unpleasant as it frequently may be, is nonetheless a good thing. In resolving this appeal, we remind the litigants and the public that if the First Amendment means anything, it means that the best response to disfavored speech on matters of public concern is more speech, not less.”

The ‘en banc hearing’ by the Court of Appeals, demanded by President Trump, was rejected on March 23rd 2020 by a vote of 7 – 2.

Indeed: “The critical question in this case is not the nature of the Account when it was set up a decade ago. The critical question for First Amendment purposes is how the President uses the Account in his capacity as a President” (p. 4 & 10/16)

The Court added then that “even if the Account (of President Trump) were a non-public forum, excluding individuals who express disfavored views is not permitted” (p. 11/16).

Citing Twitter’s ‘About’ page (“Spark a global conversation” and “See what people are talking about”) the Court notes that “public fora are used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions. That is precisely what social media do. Twitter is no exception.” (p. 12/16)

Indeed, there was a dissenting opinion (14 pages) from judges Park and Sullivan, but – as I advocated in my book ‘The force of justice’ - this only challenged the majority of the Court to motivate its opinion even more clearly.

Since then, President Trump filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with The Supreme Court

The Supreme Court ‘rescheduled’ the case already four times (last on November 18th 2020) and guess: Inauguration Day is approaching for Joe Biden.

It must however be said that after the Knight Institute prevailed in that case, the White House unblocked the plaintiffs as well as dozens of others whom the president had blocked on the basis of viewpoint.

According to The Knight Institute, The White House refused, however, to unblock two categories of individuals: those who cannot specify the tweet that provoked the president to block them, and those who were blocked before the president took office.

On July 31st 2020, the Knight Institute filed a second lawsuit against the president and his staff for continuing to block these critics.

Idem for Facebook

The Knight First Amendment Institute argued with success a similar case after a county official blocked a critic on Facebook. On Jan. 7th 2019, the U.S. Court of Appeals (Fourth Circuit Davison v. Randall No 17-2002) confirmed that the First Amendment prohibits government censorship on new communications platforms.

It decided that aspects of that Facebook page “bear the hallmarks of a public forum” and that the decision to ban the critical citizen constituted “black-letter viewpoint discrimination.”

Back to Flanders, Belgium, thanks to this ‘Cosmopolitan First Amendment’: our own Constitution, our key laws on this matter, but also basic human rights, checked by the European Court of Human Rights (Strasbourg)

The sources of our law, safeguarding free speech and free press.

The First Amendment is not only an essential part of the American ‘Bill of Rights’. We find those fundamental rights in constitutions and law in all democratic societies.

For Belgium, we read those rights in our own Constitution of Feb 7th 1831 guaranteeing the freedom of expression (art. 10, 11, 25, 26, 27, 28…), but also in the European Convention of Human Rights (Rome, Nov. 4th 1950), the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (Nice, Dec. 7th 2000) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Paris, Dec. 10th 1948).

In the US it is relevant to make out whether the account is (1) a traditional public forum, (2) a designated public forum (& subcategory: limited public forum) or (3) a nonpublic forum in order to determine how a government can engage in content-based discrimination.

In the EU a different path is followed: the rule is freedom of expression, but restrictions are possible if prescribed by law, necessary in a democratic society or meant to protect certain interests

The American ‘forum analysis’ is still relevant for us: the forum analysis has relevance in connection to access to information.

Additionally, but particularly interesting in this case is the Flemish Freedom of Information Decree (art 32 of the Constitution amended on the right of access to documents, held by the government, and as follow-up of the earlier Flemish Decree and the Belgian Freedom of Information Law of April 11th 1994) of Dec. 7th 2018 (applied since January 1st 2019) – which applies directly to this Demir case.

It is almost funny to note the tweets of the minister of Justice and Enforcement are essentially public, as they are published on that social media platform. It is somehow Kafkaesque that this public information becomes a kind of secret for the blocked citizens, only to discovered by using ‘workarounds’ as mentioned in the case against President Trump.

It is also disturbing that – to obtain that public information – journalists would be compelled to create fake or anonymous Twitter accounts: essentially this is exactly what Twitter trolls do to attack us.

This is really the legal and the real world upside down. In a free society, citizens and journalists should not be obliged to go ‘undercover’ to be able to read official statements of a minister.

So, the press’s watchdog function is harmed: blocking removes an element of accountability.

As the decision of the minister was not motivated (and not even communicated) in any way, the Belgian Law also applies (also for a Flemish minister): the Law of July 29th 1991 concerning the specific motivation of administrative acts (Wet betreffende de uitdrukkelijke motivering van de bestuurshandelingen).

A flat refusal is a no-go. Any government decision has to be motivated in form and content according to the legal criteria. This is a principle of ‘good government’ and includes criteria as reasonableness, due diligence and proportionality.

Indeed, the abrupt ‘blocking’ seems an act stemming from the Ancien Régime, when the French king announced his decisions with “Car tel est notre Plaisir” or in the ancient French of Louis XIII, advised by Richelieu “Car ainsi nous plaist il être fait” (‘Because it pleases us to do so’).

Those days are past and should not return, but we know the allergy of the Burkean neoconservative elite, inspired by ‘Reflections on the Revolution in France’ (1790) to the Enlightment and to Voltaire, but essentially, their allergy to democracy.

To complete the legal picture, we mention the Belgian Antidiscrimination Act of May 10th 2007 which also includes as a criterium of discrimination, the ‘political belief’, “the fact that someone endorses a particular political school of thought, without having to be a full member of a political party.” (source UNIA, an independent public institution that fights discrimination and promotes equal opportunities. With interfederal competence, which means that, in Belgium, UNIA is active at the federal level as well as the level of the regions and communities).

I refer here to the political incident op September 27th 2020, which prompted the abrupt blocking by minister Demir.

Finally, blocking harms journalists in their freedom of entrepreneurship (Code of Economic Law art. II.3 WER & Art. II.4, …): it is worthwhile noting 1 out of 4 journalists works as a freelancer.

The procedure: ‘see you in court’ ?

The U.S. Supreme Court plays a role that is unknown in Belgium: its judicial power encompasses what our Belgian Constitutional Court, the Cour de Cassation and the Council of State rule on but also the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

‘Precedent’ is not the (Continental) European way of judging, but exceptions exist (for decisions by the Cour de Cassation and the ECHR). And anyway, judgements published in the professional legal press (from any court) carry their weight and offer inspiration – sometimes worldwide.

The Dutch example

As The Netherlands know a similar ‘Wet Openbaarheid van Bestuur’ (WOB - Freedom of Information Law and therefore the very interesting verb ‘wobben’ ) as Belgium and Flanders, the judgement by the Dutch Council of State of March 20th 2019 (Case Nr 201800258/1/A3, confirming the judgement of the court Midden-Nederland of Nov. 28th 2017 in case 17/532) could very well inspire our Belgian Council of State.

The Dutch Court decided also sms and Whats-App messages can be subject to the (Dutch) Freedom of Information Law.

So why not Twitter messages that are originally and fundamentally public, but suddenly held ‘secret’ for some citizens ?

The archives of Twitter

Judge Buchwald noted in her Order of May, 23rd 2018 the advice of the National Archives and Records Administration that the tweets from @realDonaldTrump “are official records that must be preserved under the Presidential records Act”.

The Flemish Freedom of Information Decree of Dec. 7th 2018 I already mentioned, confirms an administrative responsibility for government agencies to manage and preserve their documents “in good, systematic and accessible conditions” (art III.81 §1).

In this digital era, this cannot be impossible, rather it is a civil servant’s duty and essential.

Our ‘Freedom of Information’ Laws cannot be effective, if communications by officials – or their official spokesman- are not preserved for history.

An illustration about this aspect in Antwerp: historians erasing history

In August and October 2017 I had a Twitter discussion about this aspect with Johan Vermant ( @JohanVermant the spokesman of Antwerp mayor Bart De Wever, president of minister Demir’s party N-VA) as I remarked mr. Vermant – a historian – systematically deleted all his tweets on short notice. On Oct. 2nd 2017 he replied “Do you have an attention problem ? I see Twitter as a medium for actua, that’s why my tweets disappear after a week. So, get back to your moral high”.

The same spokesman tweeted “Green, sewer- and left journalists fight one battle (together). Anything goes.” – about the well known dinner at the Antwerp restaurant Het Fornuis, published by the newssite Apache, itself later a victim of SLAPP).

I resumed the key question in a Twitter reply on August 16th: “Historians who delete their tweets, what to think about that? They don’t want to be held accountable for history about them ?”.

It is hardly possible to check and write the history of that kind of aggressive attacks on journalists (in that case, on Walter Pauli, Knack, who referred to the ‘Fornuis Dinner) and thus the way populists promote their policy if you are not permanent checking twitter on the original account and if necessary, save those tweets for history by taking a screencapture.

Indeed, sometimes the deleted tweets tell a more interesting story than the ones that keep receiving likes from followers, real or robots (or a partycratic mix of the two)

Facts matter, and sometimes, tweets are not only words, but a fact on itself.

Even a deleted tweet is often a very relevant fact and therefore, news.

Last, but not least, this leads us to the democratic aspect.

Time and time again, that aggressive approach seems to backfire.

Blocking is a bad political tactic.

Miami Mayor Philip Levine – a Democrat - who blocked radio host Grant Stern in 2016 – spent $29 million (a fifth of his net worth) in his unsuccessful run for governor in 2018. Stern was finally unblocked during the trial, more than a year after he filed his lawsuit in October 2016 ( source: Politico, 05/18/2018).

Kentucky Governor Matt G. Bevin – a Republican – won the court battle against blocked critics. On March 30th 2018, U.S. District Judge Gregory F. Van Tatenhove denied Plaintiffs Drew Morgan and Mary Hargis their Motion for Preliminary Injunction because “Governor Bevin has an automatic filter set up” on his accounts: “he has a specific agenda of what he wants his pages to look like and what the discussion on those pages will be”.

Among the words that administration officials would flag are: booger, carpetbagger, dictator, nimrod, tax returns, Trump, uterus, cervix, menstruation and womb.” (source: Courier-Journal 05/01/2019)

Judge Van Tatenhove concluded that “if (the Governor) wanted a truly open forum where everyone could post or comment, he could have set up his accounts to do that, but he did not. And the First Amendment does not require him to do so” (Case 3:17-cv-00020-GFVT).

You can discuss about that opinion and anyway, its scope is very narrow. But after winning that battle in the District Court, Governor Bevin – supported by the Tea Party Movement – was not reelected in 2019.

In Canada, Jim Watson, the mayor of Ottawa, ran a Twitter page on municipal affairs, notably matters that came before the municipal council. He blocked several critics of his conduct.

The three plaintiffs — lawyer and community activist Emilie Taman, Dylan Penner of the Council of Canadians and James Hutt of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers — alleged in an October 2018 lawsuit that Watson had infringed their constitutional right to freedom of expression by blocking them from his official Twitter account. They argued that his Twitter feed was a public account used in the course of his duties as mayor.

They sued on the basis that their freedom of speech guaranteed by s. 2(b) of the Charter had been impaired.

The case was settled in an early stage.

Taman said Watson likely received “some pretty strong legal advice” that his position would not hold up in court.

In a statement, the mayor’s office announced that Watson has bowed to that position in reaching a legal settlement: “Upon further reflection, Mayor Watson agrees with this view and has decided to directly address the specific concerns raised by unblocking these persons from his Twitter account”.

Watson “made peace in Twitter war” and “thanked the litigants for bringing the issue forward and vowed to encourage all councillors to maintain a high level of accessibility through social media.” (source: Ottawa Citizen Nov. 2nd 2018).

Mayor Watson was reelected.

So first, let us talk !?

As for now, although at the start of this report and complaint, I used the official terms ‘Plaintiff’ and ‘Defendant’ of course, this is not – yet – litigation.

I borrowed heavily from the American and other cases, to illustrate the legal challenge officials are risking by blocking citizens on social media.

The legal aspect is only one of many in this fundamental discussion about an open and democratic society.

Therefore, this is still first an appeal.

I do not underestimate the political difficulty of minister Demir to reconsider.

This will demand courage, in her party and in front of her own followers on social media.

But no one should enter politics without courage.

The case of Canadian Mayor Jim Watson proves this: he made peace.

Minister Demir, the Flemish minister of Justice can set a positive example of peace instead of a negative and divisive one.

In my quarter century tenure as a justice of the peace, I needed courage too.

Democracy is more than about elections and votes, just as justice is more than about procedures and orders.

Politicians and judges need also one other thing in common: to listen.

And if they can, after listening, finally also to be mild, to forgive, even to be tender (as I wrote in ‘The force of justice’) – to make peace.

So, minister Demir, with all due respect to you personally and your office, may I ask you to reconsider.

Or at least, let us still talk first.

All my professional life as a judge, I promoted dialogue and mediation. I turned the Roman proverb around and preferred: ‘Si vis pacem, para pacem’.

The need for mutual understanding is at the core of my book ‘The power of justice’ (In Dutch ‘De kracht van rechtvaardigheid’, Uitgeverij EPO 2016, In French ‘La force de la justice. Plaidoyer pour une justice plus juste’, Now Future Editions 2017).

That power of justice is the real ‘power of change’ – the election slogan of your party.

Some observers of this dispute speculate you will not respond – as you did not since September 20th - and they hope for a Belgian of Flemish ‘precedent’ after an interesting procedure with the expensive Government lawyers on your side, a bit like Goliath against David.

The idea is very appealing for legal scholars and journalists alike.

I earnestly think David stands a good chance. And David is not alone.

You could economize your lawyer costs for the Flemish taxpayer and save that court session time for the courts. Covid forces us to respect priorities.

It does not cost you anything, only a second of your time, to press that Twitter ‘Unblock’ button.

It would cost you more to talk - but still only the time to have a coffee or tea or a short walk in the Brussels Warandepark, or if you prefer, along the historic Bruges canals where I live and write – all with safe physical distancing, no worries.

It is up to you, to unblock me now in just one second, or to have a talk.

You are welcome.

And for sure, welcome back

English version - Twitter Case

1 december 2020

#justicewatcher v. ‘Flemish minister of Justice and Enforcement’ Zuhal Demir

Articles on Journalist.be